My parents rarely fought. And I’m not sure that night in 1972 would even really count as a fight at all. What I do remember is my mother raising her palms to the heavens and repeating, two or three times, “three hundred dollars, Joe? Three hundred dollars?!” That was a lot of money for anyone 45 years ago; in today’s coin, it would be about $1,500. You could buy a used car for that. For my parents – my father was a summer camp director, and my mother was a social worker – it was a significant chunk of change.

Dad had bought a camera. My mother helpfully pointed out that he already had a camera – if my memory serves, it was a Yashica Electro – and that one took perfectly serviceable pictures, didn’t it? But this one, an Asahi Pentax Spotmatic II, with two extra lenses – a 135mm telephoto and a 28mm wide angle (both Soligors) – was special. It was, my father insisted, what he needed to shoot more than snapshots, but to be a photographer.

My mother soon backed-down. Her shows of exasperation were mostly theatre meant, I suspect, to mark the moment. My parents invariably supported each other’s choices and decisions, no matter how questionable. If my father wanted to be a photographer, and he needed a $300 top-of-the-line camera to do it, then that’s what he needed. It was as simple as that, and it worked both ways.

And my father became a photographer; not in any professional sense, but as a dedicated amateur, committed to an artistic photography that usually went far beyond snapshots. He subscribed to the Life Library of Photography, a series of books by some of the greatest photographers in the world on the history, theory, and practice of the craft. He studiously pored over chapters on lighting, composition, and technique, and drew inspiration from the special yearbook.

When I look at our family photo albums today, I note a significant change – certainly an aesthetic improvement – beginning around the time my father acquired his Pentax. One photo, in particular, stands out in my memory, even though I haven’t set eyes on it for decades. In it, I am looking out the window of our place in the Laurentians in winter time; the smooth rolling snowscape beyond the lightly frosted windowpane is all gently undulating shades of dove grey and white. It’s a black and white picture, lit only by the show, and my father has managed to capture the same continuous tones of grey – from almost black on the interior side, to almost white on the exterior – in the contours of my face. It is a masterful photo, striking in its depth and simplicity, by a man who did, indeed, become a photographer.

The author (in top hat, right) posing with his father’s Pentax Spotmatic II and the Macdonald High School Yearbook photography staff. (Photo by Heather Broughton/Courtesy of The Beacon)

Photography was something that my father and I shared. My brother and I had early and continuous access to cameras – a Kodak Instamatic and a Lubitel twin-lens reflex (manufactured by Lomo) stand out in my memory – and as much film as we could ever want. During the summer, spent at Camp Wooden Acres or the YMHA Country Camp (my father was the director of both), we spent hours almost every day learning the dark arts of developing at the camp darkroom, managed by my cousin Ralph.

I still have my father’s Pentax. I used it throughout high school in the 1980s, shooting so many pictures for the yearbook that, to this day, my classmates still inevitably remember me either as “the one with the camera,” or “the one with the hair,” or both. It led me into journalism, first at Bandersnatch at CEGEP John Abbott College, then at The Link at Concordia University, and eventually to Hour, one of Montreal’s hip alternative weeklies. Photojournalism seemed like an obvious equation: I always needed access to a darkroom, and every newspaper had one, and newspapers always needed photographs.

Yet, my journalistic interests soon focused more on text than photography; it paid better, and I could tell more complex stories in words. I kept taking pictures, of course, mostly with the Ricoh KR-5 my father had given me when I started university – a gift to mark an auspicious moment and, quite honestly, he wanted his Pentax back.

To be involved in photography to any extent in the late-80s, and early-90s (when I was making the transition from photojournalist to writer) was to be acutely conscious of a seismic shift in the technology of picture-taking. Minolta’s Maxxum SLR line, which debuted in 1985, was the first hint. The Maxxum 7000 combined all of the state-of-the-art automated technologies – exposure control, automated frame advance, DX-encoded film recognition – with something new: the Maxxum could focus itself.

The new autofocus technology was far from perfect, and the Maxxum 7000 sold for $400 in 1985, about $900 in 2017 dollars, so it wasn’t for everyone. Besides, there had been consumer autofocus pocket cameras, like the Konica C35 AF, since the 1970s, and previous SLR implementations of the technology by Nikon and Pentax had been generally less than successful. Like most serious photographers at the time (I was no longer, strictly-speaking, “professional”), I took note of the novelty, imagined the possibilities, and kept moving.

What I didn’t understand was how the automated camera – either the pocket rangefinder or the SLR – would intersect with digital imaging to change everything. Indeed, my first digital camera, a Kodak DC40 rebranded the Logitech Fotoman Pixtura, impressed me mostly as a cool toy. The colours were no more impressive than its 0.4-megapixel resolution and 4MB memory, and I used it as a kind of novelty at parties and barbecues. No one doubted the future of digital photography, I just thought it was still a long way off. That, at least, is what I wrote in my computer column in the Montreal Gazette in 1995.

The irresistible logic of Moore’s Law made me a liar, or at least a fool. The vast increase in computer processing power with the concurrent plunge in cost made digital photography both ubiquitous and enormously powerful. Before long, everyone had a digital camera. They became part of every smart-and-dumb-phone, and then every computer, tablet and iPod. And they were ridiculously easy to use. You point and shoot; there’s no need focus, take a light meter reading or stand over an enlarger easel in a stuffy darkroom choking on chemical fumes.

There were and are great photographers working in the digital medium, and the technology has empowered and liberated vast numbers extraordinarily gifted artists in the same way that the first 35mm Leica moved the professional camera from the tripod to the palms of millions of hands. But the digital photography’s greatest reach was into the snapshot. Most digital pictures are taken with the 21st century equivalent of a Brownie or an Instamatic.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. Snapshots are fun and meaningful to the people who take them. They record important moments of memory, joy, sadness, and pride that we can share, relive, and reflect upon over and over again. Few people will produce images as striking, beautiful or illustrative as the work of Dorothea Lange, but they’re not trying to. Newspapers weren’t trying to. I wasn’t even trying to anymore.

Taking pictures – images, in the argot of our digital age – became so easy, and so ubiquitous that I utterly forgot about being a photographer. For more than a decade, I snapped snaps while my Ricoh gathered dust. Film photography began to seem like such a drag, as it became harder and harder to find a processing lab – let alone a darkroom – to turn silver salts into light and shadow. It was easier to record pixels.

But the ease of it had a down side for me. Digital photography, with my phone, or a pocket camera, was a practice of recording and documenting scattered moments, not creating moments that exist outside of time. Documenting events is a worthy thing to do, but it isn’t art. It isn’t the careful, magical alchemy of light, perspective, time, and motion that makes a picture a photograph. And like my father, I really wanted to be a photographer… again.

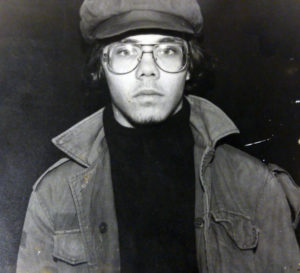

The author in an early selfie taken in the 1980s with a Pentax Spotmatic II on a tripod. Scan of a silver-gelatin print, Kodak Tri-X Pan 400.

My way back to photography began with a used Canon digital SLR eight years ago. My partner commented on the quality of the pictures that I made with it. I confessed that I used to do it for a living. When my father died in 2012, he left me his old Pentax, and I dusted off my Ricoh KR-5, and rediscovered what I imagine he always knew: with a good camera, manual focus, and only 36 frames of film, every frame counts.

While that might have seemed like a radical thought just a few years ago, it doesn’t seem so crazy anymore. I see people too young to remember the world before the digital revolution walking around with vintage Nikons and Canons that they bought for a few dollars on eBay. There are film photography classes, community darkrooms, and a thriving and growing social media network of film photographers. Just do a search for #filmphotography on Twitter or Istangram.

It probably isn’t quite correct to say that film is back – it never went away – bit it is experiencing a dramatic and steady resurgence. The major photographic film manufacturers, Ilford, Kodak, and FujiFilm, have been experiencing annual 5% market growth for the last few years. Kodak has brought back Ektachrome, the signature colour slide film it left for dead five years ago. If your pockets are deep enough, you can buy a brand-new Leica M7, or a Nikon F6 (which is temporarily sold out, due to the demand). Lomography (the company that made my old Lubitel TLR) sells new medium-format, instant, and 35mm film cameras, and the film to go with them, at more enthusiast-oriented prices.

Film will not supplant digital photography, of course, but it is just as clear that digital cameras did not, in fact, make film photography obsolete – any more than the Moog synthesizer supplanted the grand piano. Digital and film photography are different media, produced with different instruments, to achieve different results. Far from being antagonistic, they are complimentary practices. When I returned to professional photography, I found that in conversation film and digital makes me a better artist. As my father said: a photographer.